Dear Friend,

As a part of an education and fundraising initiative, Grassroots Economic Organizing Collective will have an on-demand showing of a French film about The Park Slope Food Cooperative in Brooklyn. The showing will be anytime between Nov. 13 -15, with a webinar discussion on Mon., Nov. 14 at 8 pm ET / 7 pm CT / 6 pm MT / 5pm PT. You can watch from the comfort of your home, or co-op, or other business organization in English, Spanish, French or Italian.

Park Slope Food Co-op is one of the oldest and most successful food cooperatives in the United States. It is unique because it brazenly and inexplicably breaks the co-op operating “rules” – most food cooperatives operate almost like a supermarket: you come and buy food. In some food co-ops, you pay a membership fee, which can be voluntary. At Park Slope, your membership fees are not voluntary; you cannot shop unless you work almost three hours every three months. This allows the co-op to cut one of its largest expenses – labor – by about 75%, and offer goods at a cheaper price. Its members love it!

Could this work in other places? Pros and cons?

We are inviting you to do several things: (1) Help us raise money by paying $5 to $50 to watch the film; or (2) co-sponsor the film, as a possible educational and marketing tool for your cooperative members; or (3) We also would love it if you joined us on a Zoom webinar on Nov. 14 to hear food activists, food co-op leaders and organizers and others talk about the film, the concept, and other lessons from the film. This is a fundraiser to help GEO carry out its mission to catalyze more cooperatives and other solidarity economy enterprises in this country which are needed more than ever. Your movie ticket purchased here admits you to the webinar as well. You may also check out a trailer at the Eventbrite link.

To co-sponsor, you could contribute $100 dollars and have your name on the marketing materials. You might even organize a watch party for your membership. We have included a study guide to help center the discussion around some important issues. If you would like to appear as a panelist for the discussion, please let us know.

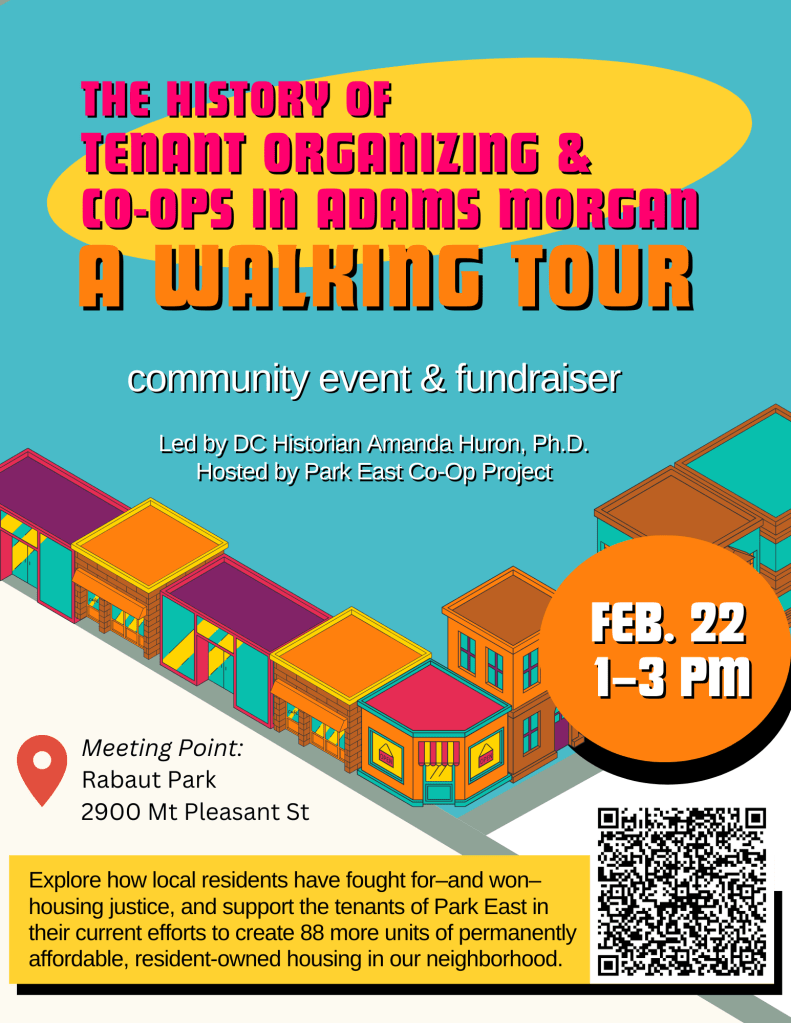

Even if you would rather not sponsor or be a part of a panel discussion, we hope that you will help us to advertise the on-demand showing Nov. 13-15 to your membership, friends and comrades and cooperators about this inspiring and exciting way to organize. To RSVP, please fill out the form. Attached is a poster that you use to publicize the event on social media.

A little more about Park Slope. There in New York City, members of all races and socioeconomic classes flock to work the co-op’s mandatory hours. The 16,000 members feel fortunate to have this opportunity to buy healthy food at lower prices. The co-op is a welcome contrast to corner stores and small supermarkets which sell substandard produce or products at very expensive prices. Park Slope is one of the few co-ops that has been able to operate according to the Rochdale Cooperative Principles, and other people in New York City and Paris have replicated the model.

Yet Park Slope Food Co-op is not without its critics. Some have called its work requirement elitist. In addition, an attempt to unionize was unsuccessful. But as one member, an older veteran on a bike, in the film says:

“The coop…is an entire community, and it actually represents a new economic system in this country. It’s going to have to [catch on] because this country is going to collapse one day if this type of system doesn’t catch on.”

To purchase tickets, please do so at Eventbrite or here to sponsor or donate to GEO.

Thank you very much, and much love!

Sincerely,

Ajowa Nzinga Ifateyo

for GEO Fundraising Circle